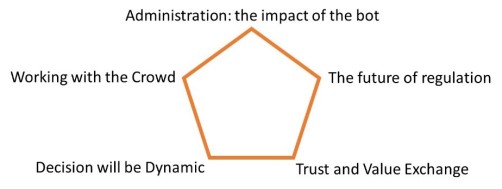

Thoughts on five themes

It would be easy to be overwhelmed by the variety and velocity of opportunities and challenges that data presents for local provision of public services.

I am making a distinction here between data and digital. For me digital has become a very broad term, relating to the modern application of computing through the vast array of devices, from the mobile phone to voice assistants. What I am focusing on in this blog is the data that rests within the systems of operation that make up public services: the dates, details and descriptions captured to allow a service to operate.

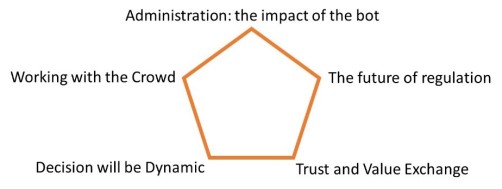

To avoid being overwhelmed, I have identified five themes of challenge and opportunity that I believe are, or will, impact on how public services are, or may, be delivered, and what this may mean for how these services are structured or provisioned in the future.

Diagram 1 – Five provocations

Regulation: The need to regulate at the pace of innovation and its adoption is fundamentally challenging how some forms of regulation are administered. Larry Downes and Paul Nunes have written about Big Bang Disruption[i], noting that the traditional adoption paradigm of Everett Rogers[ii] – of innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards – is being “collapsed” into two groups: trial users, and everybody else.

As Downes and Nunes identify, “once the right combination of technologies and business model come together in a successful market experiment, mainstream consumers move en masse to the winner.” (2013, p.5)

It is this rapid pace of adoption that is in turn leading to challenges to the way that regulation operates. This is evidenced best in relation to the emergence and rapid adoption of two “platform” businesses, Airbnb and Uber. These have been widely covered in the press, so I will only provide a short summary explanation of the approaches.

In both cases, these businesses challenge the incumbent business model of operation, for accommodation letting and taxi operations. Whilst the existing business norms have established regulatory frameworks around them, the new business models challenge this, by operating with new approaches. The obvious element is that nether firm owns the assets they trade, nor were seen to employ the operatives who operated them.

This has been well covered in the press. What has been less so, is the challenge of how to create regulatory frameworks that are flexible enough to cope with the emergence of these forms of “challenger” activity.

The challenge is that as more of this form of operation emerge, government goes through a series of “shock” responses to address the need for regulation, but at a pace that is far outstripped by the pace of innovation of the firms, and of a very different nature to that experienced in previous Industrial Revolutions.

Trust & Value Exchange – How to prove identity and share value is changing rapidly. The rise of distributed ledger technologies and Blockchain is beginning to provide significant opportunity for how aspects of transactions that require trust and identify validation could be performed. Whilst this has caught the imagination, at present, in relation to financial services, its applications in government should not be underestimated.

In November last year, the House of Lords published a report on “Distributed Ledger Technologies for Public Good: leadership, collaboration and innovation”[iii]. As long ago as 2016, the Estonian Government[iv] confirmed that it was going to use Blockchain in the recording of citizen health records.

If we look forward for a moment, it is not unreasonable to hypothesis that for rules-based transactions – such as a wide variety of benefits – that the use of distributed ledger technology could be disruptive. Imagine a situation where the processing of claims can be both accelerated and verification made more robust; where a citizen provides permission for confirmation of details about them to be shared by a wide range of organisations for the citizen’s advantage. The existing approaches to verification and validation could be fundamentally challenged, and the business model to deliver them.

Decisions will be dynamic – Decision-making will become augmented. Many council services are about the provision and maintenance of a physical asset, such as housings, parks, roads, or street lighting. With the rise of Smart Systems, currently best illustrated by Smart Lighting, there are now opportunities to augment the decisions that those who manage a system make with automated insights.

For example, a sensor in each streetlight, connected to a central control system, can provide data on the times that a light has been on, the energy consumption of the light, and the failure of the light. The implications of this, is that it can assist the managers to manage maintenance more effectively: only sending out engineers when they are required. This means that resource utility can be improved, energy consumption can be managed efficiently and the service delivered to the needs of service users.

This type of assisted, or semi-automated, support could be applied across a range of services. Christophe Guille and Stephan Zech, at Bain & Co[v], wrote a fascinating piece in 2016, about how deploying data analytics was changing the operations of public utilities.

They identify that the complexity of the data and the analytics that are applied can provide different levels of support or automation. In the military, they call this situational awareness. This ability to have closer to real-time awareness of what is going on offers significant opportunities for local service delivery, but requires new approaches to the way data is captured and used.

There are wider opportunities for this, when you start to add other datasets. You can begin to develop predictive models that allow options for intervention to be considered quicker and in ways that will allow interventions to be better understood in advance.

Working with the crowd – Decision making will become diffused. The way that opinions and views are being expressed have been fundamentally changed by the growth of social media platforms. What this means for service provision and the relationships services have with active and passive users will be critical, as it the potential to be both either disruptive or collaborative. The Attorney General’s Office in England and Wales has recognised this challenge, and launched a call for evidence[vi] in September last year to consider the impact that social media on the Administration of Justice.

A number of new approaches to gaining engagement with the populations that local services support have emerged. Perhaps the most widely referenced is work done in Bristol by their first mayor, George Ferguson. He wanted to engage with the city on what ideas it should focus to improve the city and created George’s Ideas Lab[vii]. This engagement asked people to submit ideas and then for people to vote on them, so that the crowd self-selected their preferences. This type of approach has also been used in collaborative budgeting in Liverpool[viii] and Edinburgh[ix].

These are being used currently to support the consideration of decisions, but in the future, they could be used to make the decision, particularly at a local level.

Administration: the impact of the bot – Robotic Process Automation: Simple, or rules-based, processes will be automated. The general coverage on bots is that they will lead to significant job loss. Wide ranges of observers have commented on this, including the recent Cities Outlook 2018 report[x].

Where a process is simple and rules-based, then it makes sense that these become automated, but with human oversight. However, many services involve subjective assessment. They require empathy in those that deliver the service. An opportunity that RPA and bots offer is to “free” resource to increase the number of people available to provide person-to-person support and care.

With the projected growth in support demand from an aging population and rising child levels this way of ensuring we have people available to support this. Technology does not need to be the direct solution; it can be a tool that enables in-direct benefits, by making other tasks easier. Could the use of bots trigger the opportunity for a more empathy-service-focused workforce?

Final Thoughts

In all of these examples, a consistent question arises; what is fundamentally important to us in the provision of public services? All of these technologies provide an opportunity to have a pro-social impact in the way that local public services are structured. Alternatively, they could be a challenge. What do we want?

Ritchie Somerville

Programme Advisor

Data Driven innovation Programme

University of Edinburgh

References

[i] Downes, L. and Nunes, P. (2013). Strategy in the Age of Devastating Innovation –

Big Bang Disruption. Accenture. 12 December 2013. Available at: https://www.accenture.com/t20170411T181442Z__w__/us-en/_acnmedia/Accenture/Conversion-Assets/DotCom/Documents/Global/PDF/Dualpub_13/Accenture-Big-Bang-Disruption-Strategy-Age-Devastating-Innovation.pdf

[ii] Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

[iii] Lord Holmes of Richmond (2017). Distributed Ledger Technologies for Public Good: leadership, collaboration and innovation. Lord Holmes of Richmond, 28 November 2017. Available at: http://chrisholmes.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Distributed-Ledger-Technologies-for-Public-Good_leadership-collaboration-and-innovation.pdf

[iv] Kar, I. (2016). Estonian citizens will soon have the world’s most hack-proof health-care records, in Quartz, 3 March 2016. Available at: https://qz.com/628889/this-eastern-european-country-is-moving-its-health-records-to-the-blockchain/

[v] Guille, C. and Zech, S. (2016). How Utilities Are Deploying Data Analytics Now. Bain and Co, 31 August 2016, Available at: http://www.bain.com/publications/articles/how-utilities-are-deploying-data-analytics-now.aspx

[vi] Attorney General’s Office (2017). The Impact of Social Media on the Administration of Justice. National Archives, 15 September 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-impact-of-social-media-on-the-administration-of-justice.

[vii] Bristol City Council (2014) George’s Ideas Lab. Accessed on 30 January 2018, at https://georgesideaslab.dialogue-app.com/ideas.

[viii] Liverpool Express (2013) Have a go at setting council budget. Accessed on 30 January 2018, at http://www.liverpoolexpress.co.uk/have-a-go-at-setting-council-budget/

[ix] The City of Edinburgh Council (2018) 2018/19 Council Budget Engagement. Accessed on 30 January 2018, at https://consultationhub.edinburgh.gov.uk/ce/2018-19-council-budget-engagement/

[x] Centre for Cities (2018) Cities Outlook 2018. Centre for Cities, London. Available at: http://www.centreforcities.org/publication/cities-outlook-2018/